Discovery has potential applications in artificial muscles, soft robotics and microfluidic circuitry

In a breakthrough discovery, University of Wollongong (UOW) researchers have created a “heartbeat” effect in liquid metal, causing the metal to pulse rhythmically in a manner similar to a beating heart.

In a breakthrough discovery, University of Wollongong (UOW) researchers have created a “heartbeat” effect in liquid metal, causing the metal to pulse rhythmically in a manner similar to a beating heart.

Their findings are published in the 11 July issue of Physical Review Letters, the world’s premier journal for fundamental physics research.

The researchers produced the heartbeat by electrochemically stimulating a drop of liquid gallium, causing it to oscillate in a regular and predictable manner. Gallium (Ga) is a soft silvery metal with a low melting point, becoming liquid at temperatures greater than 29.7C.

The discovery has potential applications for fluid-based timers and actuators in artificial muscles, soft robotics and “lab-on-a-chip” microfluidic circuitry.

Professor Xiaolin Wang, a node leader and theme leader at the ARC Center of Excellence for Future Low Energy Electronics Technologies (FLEET), led the research team from UOW’s Institute for Superconducting and Electronic Materials within the Australian Institute for Innovative Materials.

“By designing a special electrode and applying voltage to drops of liquid metal we were able to make the metal move like a beating heart,” Professor Wang said.

While similar heartbeat effects have been created previously in liquid mercury, this produces an erratic motion that is difficult to deactivate or control. Mercury has the added disadvantage of being highly toxic.

Liquid gallium, by contrast, is non-toxic and produces a regular motion (at frequencies ranging from 30-100 beats-per-minute depending on the influence of gravity and on the size of drop) making it potentially of far greater use.

Professor Wang said his research in liquid metals was inspired in part by biological systems and in part by science fiction, including the shape-shifting, liquid metal “T-1000” robot in the James Cameron-directed film Terminator 2: Judgement Day.

“To me, nothing is fiction – science fiction is a science fact that hasn’t been discovered yet. When I see an effect in science fiction I think about how we can create that functionality in real life,” he said.

“I don’t want to create a Terminator robot, don’t worry, but the functionality of the liquid robot can be useful in the real world so I wanted to discover more functionalities in liquid metal.

“The liquid robot from Terminator 2 had two functionalities. One was to change its shape and then recover it. The second was to change from a softer to a harder state – if you remember the scene where it extended its arm out and turned it into a sword, it turned from a soft metal to a hard one.

“Those two functionalities have been discovered. A group in China and another group in the United States discovered the first, changing shape and then recovering it, and it was my research group here at UOW that discovered the second phenomena, transition from a soft state to a hard state by applying a voltage.

“We also developed a way to form any patterns instantly, including writing, on liquid metal without touching it. My initially idea was to find a way to reproduce “crop circles” effect in our lab.

“And now we have created a functionality in liquid metal that even James Cameron wasn’t able to conceive: how to make it move like a beating heart.”

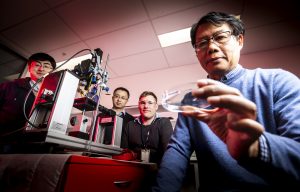

The University of Wollongong research team. From left, Fei Yun, Zhenwei Yu, David Cortie, Xiaolin Wang

While the research paper focuses on the fundamental physics of the breakthrough – understanding how and why the liquid gallium behaves in the way it does – rather than its applications, Professor Wang said there were a number of potential uses.

“There are so many applications for devices built with softer materials,” he said.

“Soft robotics is our future. To develop soft robots we need a power to drive the soft tissue to move, so very naturally we think about a soft heart for a soft robot.

“In many biological systems, in humans and animals, it is the heart that powers everything. So a metal heartbeat could be used as a pump, as the driving force to transport liquid through a channel.”

Dr David Cortie, an ISEM research fellow and one of the paper’s co-authors, said the self-regulating nature of the liquid gallium heartbeat made it a good candidate for a number of uses.

“The timing of the heartbeat occurs naturally, you don’t have to apply any complicated electronics to get the timing to work, therefore self-regulated pumping is one possibility,” Dr Cortie said.

“Something else we proposed was oscillators. In electronics you often need a timing control, for example something that sends a pulse two times per second, so by analogy, this functionality could be useful for fluid-based timers in microfluidic circuitry.”

About the research

‘Discovery of a voltage-stimulated heartbeat effect in droplets of liquid gallium’ by Zhenwei Yu, Yuchen Chen, Frank F. Yun, David Cortie, Lei Jiang, and Xiaolin Wang is published on 11 July in Physical Review Letters.

The Australian Research Council supported the research through an ARC Future Fellowship Project and an ARC Discovery Project.

Novel materials at FLEET

Prof Xiaolin Wang leads FLEET’s University of Wollongong node, as well as leading the Enabling technology team developing the novel and atomically thin materials that underpin FLEET’s search for ultra-low energy electronics, managing synthesis and characterisation of novel 2D materials at the University of Wollongong and Monash University as well as partner organisations (Tsinghua, NUS and ANSTO).

He leads FLEET’s efforts to exploit charge and spin quantum effects in magnetic topological insulators as well as fabricating high-quality samples for joint research with FLEET researchers at Monash, UNSW, ANU and RMIT.

Novel materials are key to FLEET’s quest to develop a new generation of ultra-low energy electronics.

FLEET (the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Future Low-Energy Electronics Technologies) brings together over a hundred Australian and international experts, with the shared mission to develop a new generation of ultra-low energy electronics.

FLEET (the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Future Low-Energy Electronics Technologies) brings together over a hundred Australian and international experts, with the shared mission to develop a new generation of ultra-low energy electronics.

The impetus behind such work is the increasing challenge of energy used in computation, which uses 5–8% of global electricity and is doubling every decade.

More information

- Contact Professor Xiaolin Wang xiaolin@uow.edu.au

- Dr David Cortie dcortie@uow.edu.au

- Ben Long UOW Media and Public Relations Coordinator ben_long@uow.edu.au

- Watch heartbeat effect and high resolution photographs of the researchers (available for download)

- Visit AIIM – Australian Institute for Innovative Materials

- Discover atomically-thin and other novel materials at FLEET

- Follow @FLEETCentre

- Subscribe FLEET.org.au/news